I was lucky enough to meet with several people who believe in the Jewish return to Judea and Samaria, or the ‘West Bank’ in more politically correct terms. I firmly believe all parties must be engaged in pursuit of a sustainable peace, so this was one attempt for me to walk the walk and start understanding the so-called ‘settlers.’

I first spoke with an Old City resident who has an extensive network spanning Hebron/Kiryat Arba, Susiya, Gush Etzion, Beit El, Itamar, and others. I appreciated her giving me her time, and reminded myself to stay open to listening.

Sure enough, I’ve come out of the experience utterly confused: how can you open up your heart and mind to accept someone’s decency and passion, while categorically rejecting some of their important opinions and beliefs? Having learned deep skepticism for people like Meir Kahane, Baruch Marzel, and Moshe Feiglin, how do I then keep composure with an endearing lady who tells me she personally knows these and other such folks?

Despite my discomfort, I must say I felt a warm pull by her passion. She claimed that her life’s mission was self-improvement in connection with God. She seemed to truly believe she must continue to put ‘love’ and ‘light’ into the world. And with an unwavering voice, she said all the people she knows in Judea and Samaria are full of that love and light. They are supposedly guided by pure intent and pure heart, despite what some may say about their actions. Here are roughly some quotes in which you can perhaps feel how agreeable and persuasive she is:

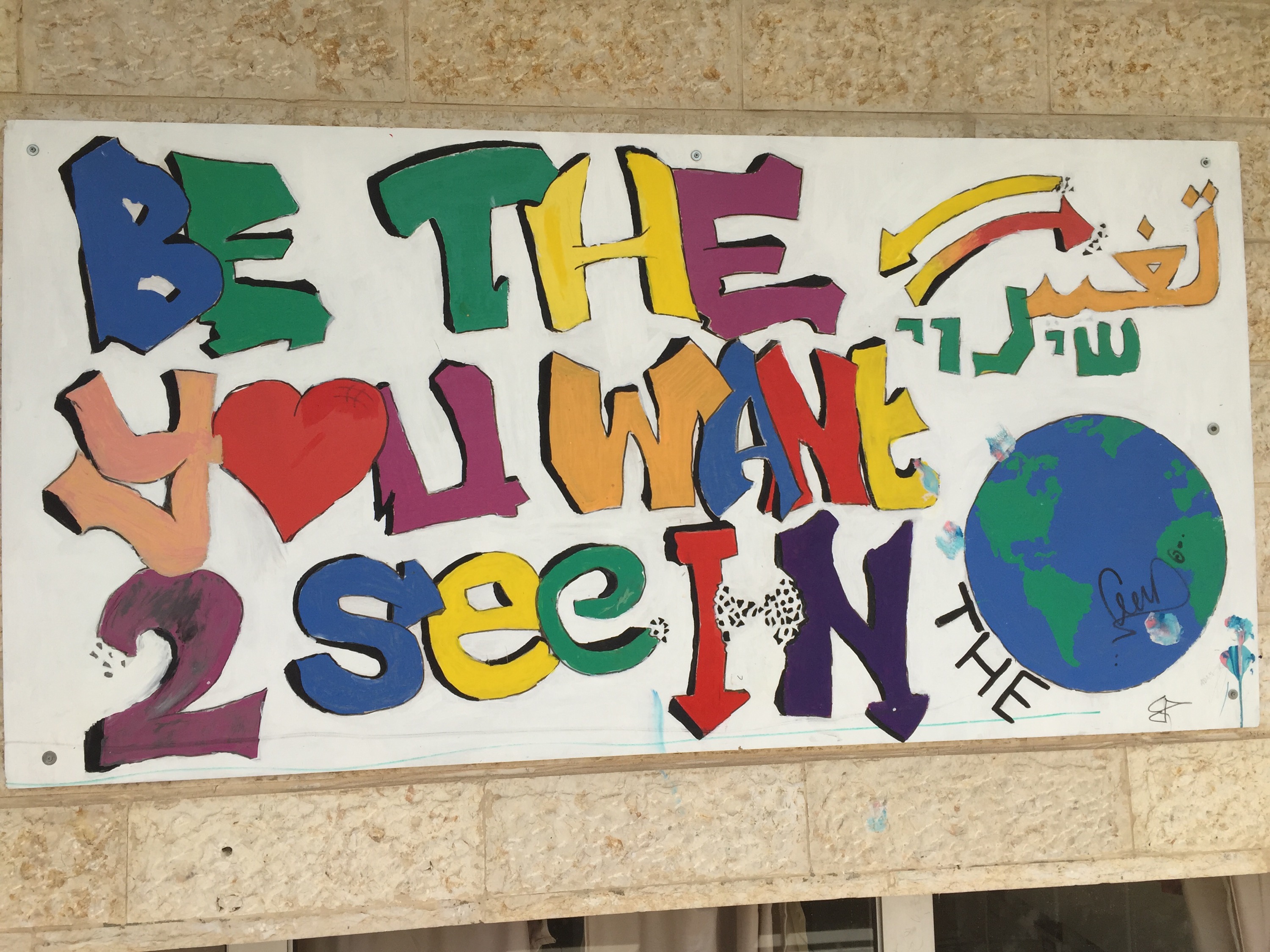

“Bringing peace isn’t about ‘conflict resolution,’ but about individual transformation through education and inspiration in the context of community and interactions within it. It can’t be done with strategy. It’s an evolution of how people see the world and how things are done. We will have to leave behind history as history, since it doesn’t and shouldn’t define the totality of reality. We have to create a reality that has never existed before, defined by our values, and that’s extremely difficult—seemingly impossible. But this is simply the only way.”

“We have to start behaving as though the Times of Redemption are already here, so that we are conditioning the world to be amenable to their arrival. We have to begin seeing through the Messiah’s eyes.”

Through this lady’s connections, I later met a lovely couple in Tekoa, part of the Gush Etzion bloc. My feelings jived with their desire for community, family, and the centrality of God in one’s life, which brought them to Tekoa from the United States. Like our friend in the Old City, they too told us about how crucial peace with oneself is for achieving any other larger-scale peace. The Jewish people must have unity first (including healing secular-religious divisions) before hoping to achieve peace with the Arabs, the husband said. I gathered that, in such a process, people’s respect for others ceases to depend on whether they agree with them.

Once the Jewish people thus makes peace with itself, it will spill over to the world. He also said the Arabs must also work on themselves, I assume in parallel. They need to begin telling each other that violence and killing are against the Quran. As long as Arabs are afraid to talk to him or his wife for fear of being called a collaborator with Israel, peace will not come.

“We’re supposed to be here. That’s clear to me.”

“You must be a light unto all people you meet.”

Perhaps you can’t really get a sense from these quotes. But I can’t shake his clarity from my mind. How he can say with quiet confidence that extremism in Judea and Samaria hasn’t seen historic growth. How the BDS movement will hurt its adopters the most, not Israel, by giving up Israel’s “computer chips and cures for cancer.”

Listening to these individuals in Tekoa and the Old City, I felt I was entering a world existing on an entirely other plane than political labels or political accountability. It’s a world where everything is having faith in the long-term process. Where constituents don’t vote for a political settlement promising ‘peace’ in the short term. It’s a world where people are reaching for something that doesn’t yet exist, where family and community serve as an incredible source of support for achieving the impossible.

Is this really the same world that periodically gives rise to those twisted acts we hear about in the news? Is it at all because people are judged more by the ‘pure intent’ of their actions rather than by their immediate physical consequences?

If, according to your worldview, your actions cannot truly be judged by secular law or by how they affect a political ‘peace process,’ then at what point do you stop and evaluate your actions? How much adversity (some of it self-wrought) will your faith help you cope with before you rethink your religious convictions?

I come away with respect for these people, including for the spiritual force that they’ve found for themselves. But I still hunger to understand whether they see their faithful actions as having so far contributed to their ideals such as equality, social justice, and dignity for all in the land between the River and the Sea.