Volunteering at a Jewish-Arab integrated school was my most joy-filled time in Jerusalem. I feel that, despite all the dehumanization of both Jews and Arabs in the Holy Land, one can wash away prejudice by interacting with the children of ‘the other side.’ I probably couldn’t have engaged with this land in certain meaningful ways without also having been inside the walls of this school. For example, away from the godforsaken ‘adult’ world of strife outside, I saw how kids made real bonds across the divide: through the shared experience of classroom games, soccer during breaks, and together earning the teacher’s ire and together facing her chastisement.

It didn’t take long for questions to emerge in my mind, though: namely, the predominance of Hebrew despite the intended bilingualism, and the limits to sharing both the Israeli and Palestinian narratives.

I sat down with one of the teachers to hear more:

“If the school were perfect, Hebrew and Arabic would be fifty-fifty,” she said, lamenting how if one kid speaks Hebrew, then all the children cascade into speaking Hebrew. Similarly, when staff at a meeting are mixed, then that meeting by necessity is conducted in Hebrew. She didn’t think the Palestinian staff had negative feelings about this, but she couldn’t be sure if this was always the case.

We talked about how most Jewish Israeli students don’t manage to learn Arabic well enough to have natural conversations in the language. I surmised it might take more structured opportunities for them to apply their Arabic as a living language. Moreover, more Jewish Israeli adults who speak Arabic must be sorely needed as role models for the pupils to gain the self-confidence to hone their ability.

We later talked about how the school handles national days of commemoration. How on Yom Hazikaron, or the Israeli Memorial Day for fallen soldiers, Palestinian staff and students do not stand for the siren marking the nationwide minute of solemn silence. How, for a time, many Palestinian children stopped coming to school on this day of commemoration. (By contrast, they do stand in silence for Yom Hashoah, or Holocaust Remembrance Day.)

“You haven’t seen a single person stand up for the siren, even by accident?” I asked.

“No. It’s like it’s ingrained in everybody. Even if people identify with the sadness, they simply can’t take part.”

In that moment, I contemplated what she was introducing to me, something perhaps ineffable. It was a capacity for people who have hurt each other to empathize, but short of crossing a line – a line Israelis and Palestinians drew together in blood and tears.

The teacher told me that last year, the school instituted a change to have its commemoration of the Nakba together with Yom Hazikaron. She described the undeniable change she sensed among the Palestinian children, a feeling that their presence mattered and was being validated on Yom Hazikaron.

“I think the commemoration allowed them to be seen and allowed their self-esteem to be recognized. You know, I think recognizing each other’s self-esteem is half the battle.”

I also thought about the act of accepting Israelis as they all stood up to honor their fallen brothers and sisters. This, too, is making room for the other’s self-esteem. In both directions, there can be room to acknowledge the uncompromiseable core of the other’s self-worth.

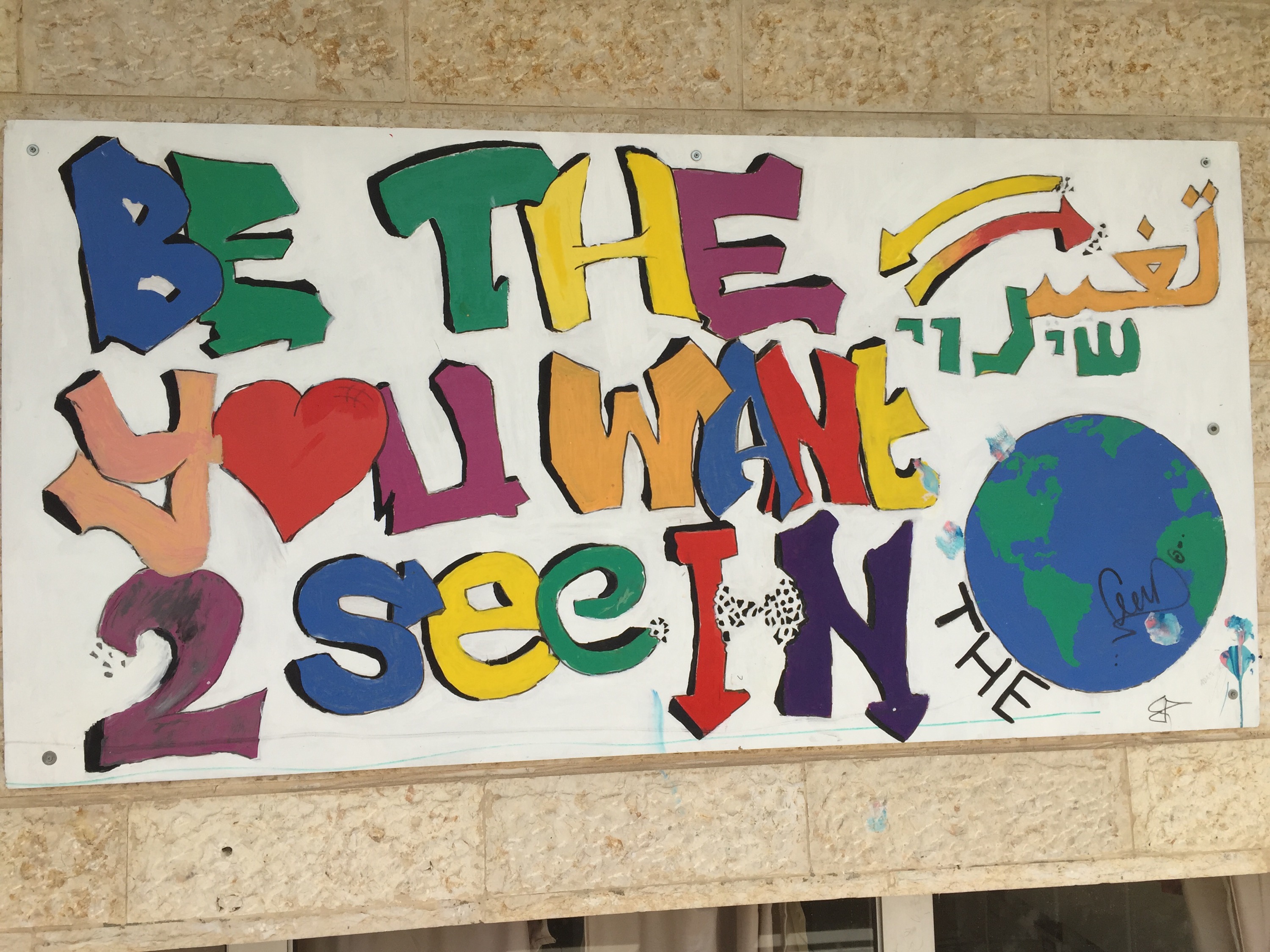

What a place, I thought to myself. In its walls, students are stretching their minds. They’re recognizing that mutual dignity is created not only by bilingualism and multiculturalism, but also by validating the other’s narrative of struggle. To survive, resist, and express one’s right to dignity.

I asked her how she’s changed after ten years at the school. Unassuming and ‘unproselytizing,’ she told me that the school simply opened her eyes. It allowed her to live her ideals. In the past, she’d believed in equality but “had never talked to an Arab kid.” Now, she knows she could never go back to teaching at her previous school. Despite having loved her job, she would not be able to go back to an atmosphere in which people believed Israel could supposedly do no wrong.

While believing in Israel as a state, she was yearning for her country to grow into the democratic and tolerant ideals it set for itself at independence.